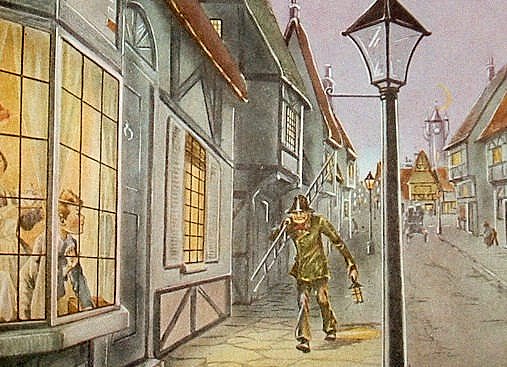

Lamplighters appear as sentimental and nostalgic figures in literature for and about children. Maria Susanna Cummins's 1854 novel The Lamplighter tells the story of an orphan girl rescued from an abusive household by a member of said profession. Cummins's novel was so popular that for a time it was second only in sales to Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). Robert Louis Stevenson's poem "The Lamplighter" in A Child's Garden of Verses (first published in 1885 as Penny Whistles) describes what may be Stevenson's own childhood growing up in Scotland, where the lamplighters were called leeries.

My tea is nearly ready and the sun has left the sky;

It's time to take the window to see Leerie going by;

For every night at teatime and before you take your seat,

With lantern and with ladder he comes posting up the street.

Now Tom would be a driver and Maria go to sea,

And my papa's a banker and as rich as he can be;

But I, when I am stronger and can choose what I'm to do,

O Leerie, I'll go round at night and light the lamps with you!

For we are very lucky, with a lamp before the door,Both Cummins and Stevenson describe children who take pleasure in waiting each evening to see the local lamplighter passing through on his rounds and lighting the nearest lamp. These episodes seem to suggest a common childhood experience in the pre-electric era, as well as a common trope in children's literature--that there is a special, sentimental relationship between children and working class adults.

And Leerie stops to light it as he lights so many more;

And O! before you hurry by with ladder and with light,

O Leerie, see a little child and nod to him tonight!